Key Takeaways

- You can make your physique more attractive by improving your muscle proportions according to a formula known as the Grecian Ideal.

- This Grecian Ideal states that your flexed arms and calves should be 2.5 times larger than your non-dominant wrist, your shoulders should be 1.618 times larger than your waist, your chest should be 6.5 times larger than your wrist, and your upper leg should be 1.75 times larger than your knee.

- Most people don’t have the genetics to reach these targets perfectly, but everyone can get close enough to have an outstanding physique (keep reading to learn how!)

Let’s face it: At least half of the reason most of us work out is to look great. You know, muscular, lean, proportional . . . “aesthetic” as the “fitfluencers” like to say. To be specific:

- Broad shoulders with bulging biceps and triceps

- A big, flat chest on top of a V-tapered torso

- A narrow waist and ripped core

- Developed and defined legs

And there’s nothing wrong with that.

People are always searching for “hacks” and shortcuts to live a better life, and looking good is a big one.

When you’re physically attractive, you have more confidence and people like you more and treat you better, and this positively impacts every aspect of your life.

How do you build a beautiful body, though?

“Bodybuilding,” of course, but these days, that’s a loaded term, because top bodybuilders are all about packing on freakish amounts of mass in a quest to resemble a hybrid between a human and Belgian Blue cow.

That wasn’t always the case.

Once upon a time, before steroids, bodybuilders wanted to look like athletes in their prime or ancient warriors, not hulking mountains of anabolic-infused muscle.

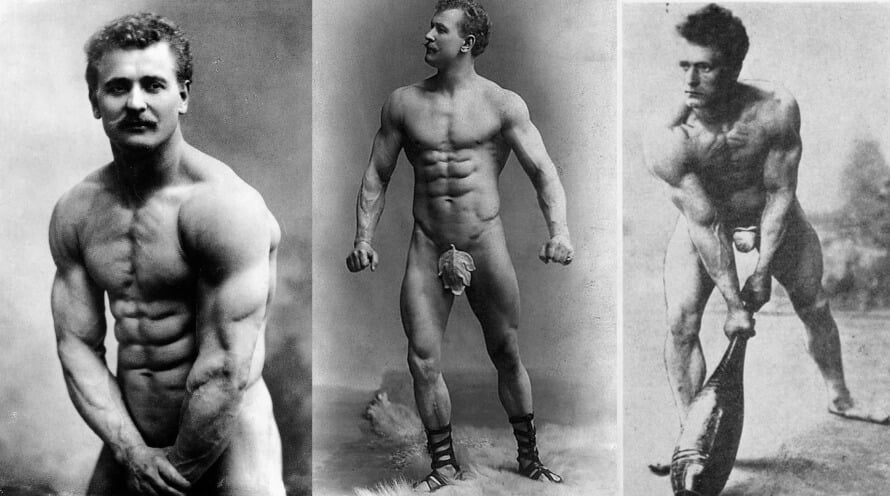

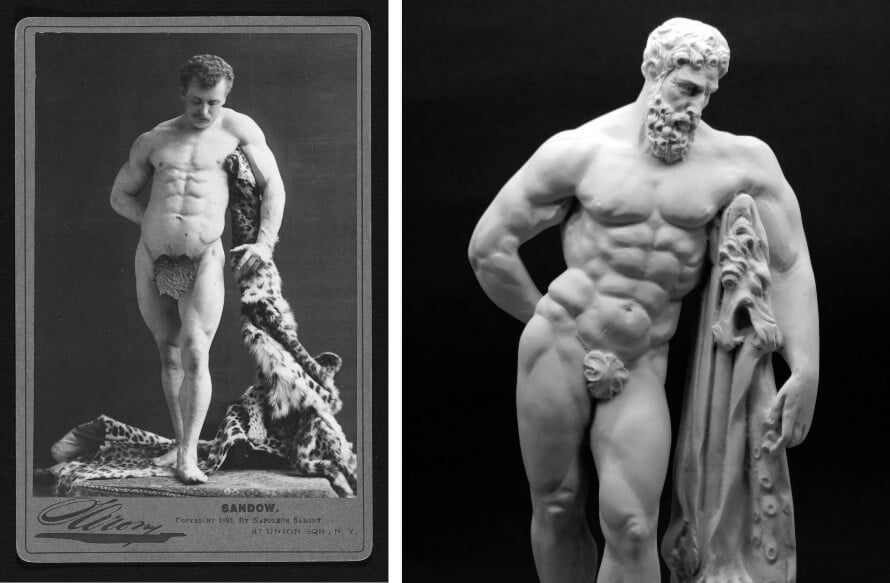

For example, check out Eugen Sandow again from the late 1800s, before testosterone was synthesized:

Small and fat by today’s bodybuilding standards, but his physique was outstanding in terms of overall muscularity, proportions, and body fat levels, and represents the pinnacle of what most natural bodybuilders can hope for.

And that’s okay with most guys, who would pike a pod of baby seals to look like Eugen.

Another good example is the bodybuilding pioneer Otto Arco, who achieved this in the early 1900s:

And finally, here’s George Hackenschmidt, a contemporary of Sandow and Arco (and the inventor of the barbell bench press):

These men couldn’t just dial up their doses of #dedication to gain endless muscle, so instead, they pursued the ideal relationship between size and symmetry and became literal embodiments of the essence of male beauty—the right balance of overall muscular development, proportion, and definition.

What’s more, nothing they did is out of reach for the average guy.

While you and I can’t forge our bodies into carbon copies of Eugen’s, Otto’s, or George’s, we can get to their level through enough hard work and patience.

And that’s what this article is all about—a deep dive into what creates that look and how to get there.

It’s far simpler than you might think, too.

The key to it all is the application of a mathematical relationship known as the Golden Ratio.

In this article, you’re going to learn . . .

- The ancient formula that dictates the proportions of the “ideal” male body

- How to compare your body to these standards to see what parts need the most work

- How close you can expect to get to these numbers based on your genetics

- And finally, how to eat and train to build the ideal male body.

Let’s get started.

- The Golden Ratio and the Ideal Male Body

- How to Achieve the “Grecian Ideal”

- Comparing Your Body to the Grecian Ideal

- How Close Can You Get to the Grecian Ideal?

- The Bottom Line on the Ideal Male Body

- What do you think of the formula for the ideal male body? Have anything else to add? Lemme know in the comments below!

Table of Contents

Want to listen to more stuff like this? Check out my podcast!

The Golden Ratio and the Ideal Male Body

After spending most of his life constructing siege weapons, fortresses, and camps to support Julius Caesar’s campaigns across Europe, the architect, author, and engineer Marcus Vitruvius published the book De Architectura.

It’s since become one of the most important sources of modern knowledge of Roman building methods, planning, and design, including blueprints and materials for towns, temples, civil and domestic buildings, pavements, aqueducts, and more.

Vitruvius’ publication also included ideal human proportions, which he believed should inform the structure of sacred temples.

In fact, he claimed the human body corresponded to the hidden geometry of the universe itself and thus was a microcosmic representation of the physical realm.

Over fifteen hundred years later, sometime around 1487, Leonardo da Vinci drew the human figure per Vitruvius’ observations and named it the Vitruvian Man.

Like Vitrivius, da Vinci was fascinated with human anatomy and believed that “man is a model of the world.”

The Vitruvian Man would become an exemplar of perfect male proportions, and researchers would later discover that its balance and beauty stemmed from its expression of a mathematical relationship known as the Divine Proportion or Golden Ratio.

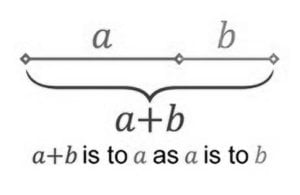

Euclid first defined the Golden Ratio in his tour de force Elements, published in 300 BC. The concept is simple: two quantities are in the Golden Ratio if the ratio of the sum of the quantities to the larger quantity is equal to the ratio of the larger quantity to the smaller one.

Visually, it looks like this:

And numerically, it’s expressed like this: 1:1.618 (1 to 1.618). In the case of the above image, b is 1 unit long, and a is 1.618 units long.

The fascinating thing about the Golden Ratio is it isn’t an abstract thought experiment—it appears to be a natural law.

Scientists have found it everywhere in nature, including the arrangement of branches along the stems of plants and in the veins of leaves, the skeletons of animals and disposition of their veins and nerves, and the composition of chemical compounds and the geometry of crystals.

Researchers have recently reported the ratio present even at the subatomic level.

Nowhere is the Golden Ratio more exemplified than in the human body, however.

The face, for instance, abounds with examples of the ratio. The head forms a golden rectangle with the eyes at its midpoint. The mouth and nose are each placed at golden distances between the eyes and the bottom of the chin. The spatial relationship of the teeth and construction of the ear each reveal the ratio, too.

We also find the Golden Ratio in the overall proportions of the human body, the different lengths of the finger bones, the makeup of the feet and toes, and even the structure of DNA.

Additionally, as da Vinci observed so long ago, the more the body embraces the Golden Ratio, the more beautiful it’s perceived to be.

And so for centuries, artists used it to design more appealing figures, while more recently, plastic surgeons and cosmetic dentists have used it to create more attractive faces and mouths.

Some scientists have pointed out that you can find all kinds of various equations in nature if you look for them hard enough, but the Golden Ratio is so pervasive it’s impossible to dismiss it as coincidence.

The Golden Ratio is useful for our purposes, too.

By adjusting the size of various body parts in relation to others to align with this ratio, we can improve our visual attractiveness.

This isn’t a new concept, either.

Eugen Sandow was the first person to popularize this approach to bodybuilding, and he used it to build one of the most impressive physiques of his time.

Summary: The Golden Ratio is a special geometric relationship found in nature and used by artists, architects, and plastic surgeons to create a beautiful sense of symmetry and proportion. By applying this ratio to your muscles, you can make your body more attractive.

How to Achieve the “Grecian Ideal”

Sandow was renowned for his resemblance to classical Greek and Roman sculptures, which were celebrated for their portrayal of the ideal male body—a small waist that expands upward into a broad, muscular chest and shoulders, balanced by a pair of powerful legs.

For instance, here’s Sandow doing his best impression of Glykon’s statue of Hercules, which depicted the apogee of physical perfection among the ancient Greeks:

This striking resemblance was no accident.

Sandow measured the statues in museums he aspired to look like and found they had certain proportions between body parts in common. From this observation, Sandow developed a blueprint for the perfect physique, which he called the “Grecian Ideal.”

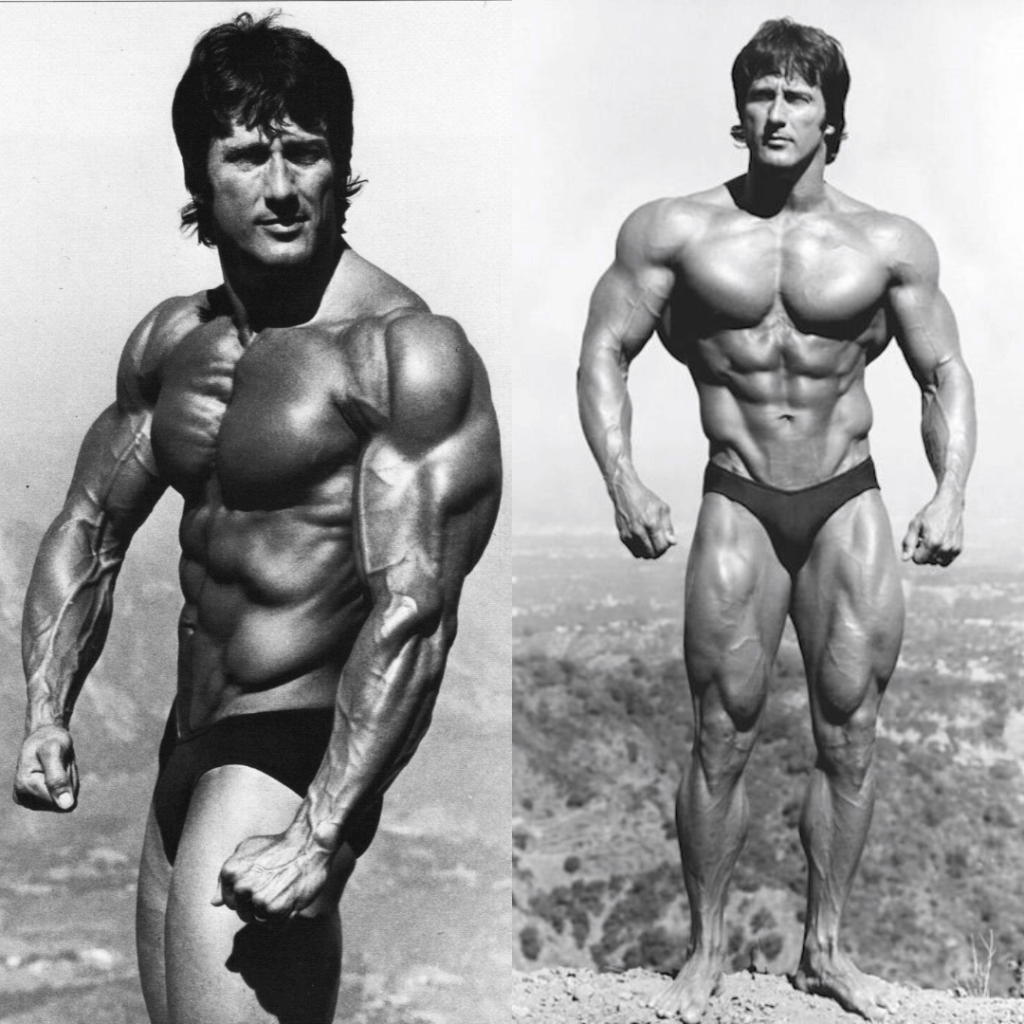

Although he didn’t know it, his system revolved around the Golden Ratio, and it later served as a model for future bodybuilders who became known for their proportions, like Steve Reeves, Frank Zane, Serge Nubret, Bob Paris, and Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Perhaps no one better exemplified this approach to bodybuilding better than Frank Zane, who had truly outstanding proportions and symmetry:

So what is this system? And how can it help us look like a Greek sculpture, too?

It starts with establishing reference points—parts of the body that’ll determine how large other parts should be to achieve a pleasing whole.

Some of these points, such as the wrist and knee circumference, don’t change in size as you age or gain or lose body fat or muscle. Others, such as the waist, do.

For example, by measuring your wrist size, you can establish how large your upper arms should be, and from that measurement how big your calves should be. Your knee size determines how large your upper legs should be, and your waist size tells you how broad your chest and shoulders should be.

In other words, the recipe for the ideal male physique is a set of simple, formulaic relationships between body parts, starting with . . .

1. Your flexed arms should be 150% larger than the circumference of your non-dominant wrist (wrist circumference x 2.5).

To measure the smallest part of your wrist, find the bony lump on the outside of it (the styloid process), open your hand, and wrap a tape measure around the space between that lump and your hand.

And to measure your flexed arms, wrap the tape around the largest part of them (the peak of your biceps and middle of your triceps).

Some people say you should only measure your non-dominant arm, but I like to measure both for more accuracy. This also helps you identify any muscle imbalances between your right and left arms.

Take these measurements under normal conditions, too (without a pump or carb loading to increase your muscle size). Otherwise, your numbers won’t reflect your everyday level of muscularity, which is what matters most, not how you look for the thirty minutes following a workout or large meal.

Some people also say this wrist-to-arm ratio applies to an unflexed arm—not flexed—but I disagree.

My wrist circumference is 7 inches, while my arms are 17 inches flexed and 14.5 inches unflexed, and they look balanced compared to my chest and shoulders.

If I were to assume this ratio refers to an unflexed arm, however, my arms would have to swell to about 17 inches unflexed and 20+ inches flexed, which would look ridiculous and require copious steroid use.

So, even if you lack a prominent biceps peak, stick with flexed measurements.

2. Your flexed calves should match your flexed arms.

To measure a flexed calf, raise your heel, press your toes into the ground, and wrap a measuring tape around the largest part of the muscle.

3. Your shoulder circumference should measure 1.618 times larger than your waist (waist circumference x 1.618).

This produces the coveted V-taper that scientific research has proven to be attractive to women.

To measure your waist circumference, circle your waist with a measuring tape at your natural waistline, which is above your belly button and below your rib cage. Don’t suck in your stomach.

And to measure your shoulder circumference, stand upright with your arms at your sides (no flaring your elbows or spreading your lats), and have a friend wrap a tape around your shoulders and chest at its widest point. This is usually right around the top of your armpits.

4. Your chest circumference should be 550% larger than the circumference of your non-dominant wrist (wrist circumference x 6.5).

There are other ways to reach the ideal chest measurement, but this is the easiest and most reliable one.

To measure your chest circumference, stand upright with your arms at your sides (again, no flaring your elbows or spreading your lats), and have a friend place a measuring tape at the fullest part of one of your pecs and wrap it around the other, under your armpit, across your shoulder blades, under your other armpit, and back to the starting point.

Then, take in a normal breath (not overly expanding or deflating your chest) and note the result.

5. Your upper leg circumference should be 75% larger than your knee circumference (knee circumference x 1.75).

A true Übermensch has an impressive set of wheels, and if you achieve this ratio, you’ll check that box.

To measure your knee circumference, extend your leg and wrap a measuring tape around the middle of your kneecap.

To measure your upper leg circumference, flex your upper leg and wrap a tape around the widest part of your thigh and hamstring.

Comparing Your Body to the Grecian Ideal

Before you break out the tape measure, here’s an important caveat: if your body fat level is too high, your measurements will be skewed, and this will affect some areas of your body more than others.

Thus, if you want to use everything you’ve just learned to see which parts of your body need improvement the most, you’ll need to get lean first. Specifically, I recommend you get down to somewhere around 10 to 12 percent body fat, which is lean enough to showcase your physique without being impractical or unhealthy.

As for taking your measurements, it’s straightforward.

Take the following measures first thing in the morning, before eating or working out, and note down your numbers:

- Your non-dominant wrist circumference

- Your arm circumference (both arms)

- Your shoulder circumference

- Your chest circumference

- Your waist circumference

- Your upper leg circumference (both legs)

- Your non-dominant knee circumference

- Your calf circumference (both calves)

Then, compare your figures to the formulas given earlier and note your strengths and weaknesses.

For example, here are my current measurements:

- 7-inch non-dominant wrist

- 17-inch arms

- 51-inch shoulder circumference

- 43-inch chest circumference

- 32-inch waist

- 24-inch upper legs

- 14-inch non-dominant knee

- 15-inch calves

And here are my “ideal” numbers:

- 17.5-inch arms

- 52-inch shoulder circumference

- 45.5-inch chest circumference

- 25-inch upper legs

- 17.5-inch calves

According to the above, I need to increase my shoulder, chest, upper leg, and calf measurements, and I agree.

My shoulders can always use more goosing. (You can’t have shoulders that are “too big” as a natural weightlifter).

I’m happy with my chest development, but I could go in for more lats (which would expand my chest measurement).

Per bodybuilding standards, my upper legs are a little behind, but I’m happy with where they are and, frankly, don’t want bigger upper legs. (It’s already hard enough to find jeans that fit!).

And my calves need some size, but thanks to my genetics, that’s a tough row to hoe.

This brings me to another important issue.

While the Grecian Ideal gives helpful reference points, don’t treat it like dogma. Sometimes, as in my case, the targets can be unrealistic (I’ll never have 17-inch calves) or excessive (my chest already looks strangely big for my size, so there’s no sense in trying to add more).

So, take your measurements, compare them against the model, see where you agree, and adjust your training accordingly (if necessary).

Summary: To achieve the ideal male body, you want your flexed arms and calves to be 2.5 times larger than your non-dominant wrist, your shoulders to be 1.618 times larger than your waist, your chest to be 6.5 times larger than your wrist, and your upper leg to be 1.75 times larger than your knee.

How Close Can You Get to the Grecian Ideal?

Applying the Golden Ratio to our body’s proportions gives us objective standards to strive for, but as you know, our genetics will largely determine how close we can get to achieving those goals.

And while there’s no way to calculate with absolute certainty how big each of our muscle groups can grow, there are formulas that give reasonable estimates.

For instance, thanks to the work of Dr. Casey Butt, you can use your height, body fat percentage, and wrist and ankle measurements to gain insight into how big you’ll be able to grow your chest, biceps, forearms, neck, thighs, and calves.

Check out this article to learn more about how this works:

⇨ Here’s How Much Muscle You Can Really Gain Naturally (with a Calculator)

Here’s a calculator based on Dr. Butt’s insights:

To be sure, this isn’t a perfect tool, and it represents best-case outcomes, but it’ll give you a realistic estimate of how close each of your muscles can get to achieving the Grecian Ideal proportions.

For example, I’m 6’1, about 10 percent body fat, and my wrist is 7 inches and my ankle is 8 inches.

According to Dr. Butt’s calculator, here are the maximum measurements I could hope to achieve under ideal circumstances:

- Chest: 47 inches

- Biceps: 17.4 inches

- Forearms: 14 inches

- Neck: 17 inches

- Thighs: 24.3 inches

- Calves: 16.3 inches

As I said a moment ago, it’s probably best to scale these numbers down by about 5% (which the calculator does for you), which gives the following:

- Chest: 44.6 inches

- Biceps: 16.6 inches

- Forearms: 13.3 inches

- Neck: 16.2 inches

- Thighs: 23 inches

- Calves: 15.5 inches

Those numbers are spot-on and represent more or less what I’ve been able to achieve in about a decade of proper diet and training (and two decades in all).

Accordingly, it’s fair to assume most of my body parts are about as big as they’ll ever get.

This agrees with similar calculations of my genetic potential for whole-body muscle gain that say there’s little, if any, muscle left for me to gain, no matter what I do in the gym.

None of that means my training has to become a dreary, pointless grind, though. It just means my goals and expectations have needed to evolve with my body, and I’ve had to learn to appreciate what I’ve got and find a deeper motivation to keep going than bigger biceps.

This can take many forms.

It can be feeling more confident and competent inside and outside of the gym, being more productive at work, setting a good example for your kids, tackling new physical challenges like sports, hiking, biking, or running, avoiding disease and dysfunction, or slowing down the processes of aging and retaining a youthful vitality.

For me, it’s several things.

It’s doing workouts I enjoy that’ll allow me to stay in peak shape and health for the rest of my life, without pain or injury.

It’s keeping the spark alive in my marriage and helping my kids develop a positive relationship with food and exercise—lessons they can pass on to their kids, too.

It’s a matter of personal pride and responsibility, of physically expressing my values and worldview, of producing and presenting my best self.

I view all that as a privilege and prize, not a compromise or comedown. Something to celebrate, not tolerate.

And if these numbers have let some of the air out of your balloon, take heart.

With the right plan and enough hard work, just about everyone can get a few key muscle groups like the chest, shoulders, and arms up to scratch, and this alone is enough to build a physique that’s head and shoulders above the average weightlifter’s.

If you can do that (and you can), plus ensure your legs aren’t a glaring weakness and then maintain a relatively low body fat percentage, you’ll look fantastic.

Summary: Depending on your genetics, you may never be able to fully embody the Grecian Ideal, and that’s okay. Achieve what you can and chances are you’ll wind up with an impressive physique.

The Bottom Line on the Ideal Male Body

If you want to build a fantastic physique, you must do more than haphazardly lift weights, eat food, and take supplements.

That’ll get you size, but not proportion and symmetry, which is why you need to systematically develop your muscles and your physique as a whole.

That’s why you need to pay special attention to how you develop your muscles and strive for proper proportion and symmetry.

You can use a collection of simple standards known as the Grecian Ideal to help with this.

This Grecian Ideal states that your flexed arms and calves should be 2.5 times larger than your non-dominant wrist, your shoulders should be 1.618 times larger than your waist, your chest should be 6.5 times larger than your wrist, and your upper leg should be 1.75 times larger than your knee.

Most people don’t have the genetics to reach these targets perfectly, but everyone can get close enough to have an outstanding physique.

All that takes is a few years of following well-designed strength training programs and effective meal plans.

This article is from the second edition of my bestselling fitness book for experienced weightlifters, Beyond Bigger Leaner Stronger, which is now live everywhere you can buy books online. Click here to learn more.

What do you think of the formula for the ideal male body? Have anything else to add? Lemme know in the comments below!

+ Scientific References

- Horvath T. Physical attractiveness: The influence of selected torso parameters. Arch Sex Behav. 1981;10(1):21-24. doi:10.1007/BF01542671

- Liu Y, Sumpter DJT. Is the golden ratio a universal constant for self-replication? PLoS One. 2018;13(7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200601

- Coldea R, Tennant DA, Wheeler EM, et al. Quantum criticality in an ising chain: Experimental evidence for emergent e8 symmetry. Science (80- ). 2010;327(5962):177-180. doi:10.1126/science.1180085

- Lucker GW, Beane WE, Helmreich RL. The strength of the halo effect in physical attractiveness research. J Psychol Interdiscip Appl. 1981;107(1):69-75. doi:10.1080/00223980.1981.9915206